You can download the Good Design + Sustainability document here or find the full text below.

The Office of the Victorian Government Architect provides strategic advice to government about architecture, landscape architecture and urban design.

Acknowledgement

The OVGA acknowledges the traditional Aboriginal custodians of Country throughout Victoria. We respect their deep knowledge of Country and practices that support living in balance with the natural world. Project teams are encouraged to work closely with Traditional Owners to understand and design with Country, enriching the approach to sustainability.

About this publication

Victoria is committed to creating a high-quality, sustainable built environment, and reducing carbon emissions towards its 2045 net zero carbon target. To do this, government itself must be a smart client when procuring critical infrastructure such as housing, schools, hospitals and rail projects.

Good Design and Sustainability helps decision makers, project managers and designers deliver public projects in line with the government's aspirations and best practice. It provides guidance on how to set objectives, principles and targets, and sets out processes to achieve cost-effective and high-performing buildings, infrastructure and public spaces.

Good Design and Sustainability is based on experience and evidence. We suggest reading it alongside our related publications:

• The Case for Good Design – the evidence compendium

• Government as Smart Client – the procurement guide

• Good Design Issue 01 – the principles of good design

• Other Good Design publications – for specific building types

(Cover) Monash University Gillies Hall

00 COMPLETED: 2019, ARCHITECTURE: Jackson Clements Burrows, CLIENT: Monash University, INNOVATION: Cross-laminated timber (CLT) structure 50% reduction of embodied carbon from structure, RATING: Passive House Certified.

Gillies Hall student accommodation is one of Australia’s largest timber and Passive House certified buildings. The use of structural crosslaminated timber (CLT) panels halved the amount of embodied carbon compared with typical concrete construction. The Passive House standard ensures high energy efficiency, indoor air quality and comfort.

Shaped through strong partnerships with Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation and Court Services Victoria, the building contributes to the civic revitalisation of Bendigo's city precinct.

Leadership

The government develops policies and regulations for the built environment, and is also the largest procurer of design services and construction. In this unique position, it can set standards and drive innovation. As a result, the public can benefit from better buildings and places as well as more

sustainable and cost-effective assets.

Exceeding the Commonwealth’s promise to cut carbon emissions 45-50% by 2030 (compared to 2005)1 , the Victorian Government is committed to reducing carbon emissions 75–80% by 2035 and to zero by 2045.2 At a national level, this transition is supported by the Commonwealth’s Trajectory for low-energy buildings 3and the Climate Change Authority's Net-Zero Built Environment Sector Pathway.4

At the same time, we must build many more homes, hospitals, schools and other critical infrastructure. Collaborating with industry, government has the opportunity to drive the shift to greater productivity as well as zero carbon.

Industry associations such as the Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council, Property Council of Australia and Australian Institute of Architects also recognise that innovation in sustainability is critical to the future of our built environment. By working together on key issues, both industry and government can drive change and deliver greater benefits to the community.

When done well, sustainable design enhances people’s lives and generates greater value, while addressing the critical issues of carbon, resilience and biodiversity.

The Tarakan Street social and affordable housing project comprises 130 tenure-blind homes arranged around existing native trees.

Policy

Victoria

Climate Change Act 2017 and Strategy

Sustainable Investment Guidelines

Recycled First Policy

Australia

Net Zero Built Environment Sector Pathway

Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings

National Australian Built Environment Rating System

Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council

Green Building Council of Australia

Infrastructure Sustainability Council of Australia

International

International Panel on Climate Change

International Energy Agency

UN Sustainable Development Goals

World Green Building Council

Responding to the climate crisis

Net zero emission buildings

Buildings are the world’s largest cause of carbon emissions yet also provide the greatest and most cost-effective opportunity for emissions reduction. Of the 39% of global emissions associated with buildings, 28% occur from operations and 11% from construction.5

The International Energy Agency warns that: 'The building sector is not on track for net zero by mid-century, with emissions growing at an average of 1%

per year since 2015... To achieve net zero by 2050, all new buildings need to be net zero from 2030. A significant leap from less than 5% of new buildings today.'6

The good news is that we already know what we need to do to get there. Net zero emission buildings are simply highly efficient, all electric and powered by renewable energy. To support an electricity grid that is rapidly transitioning to renewable energy, buildings also have a role in stabilising electricity peaks and troughs. This can occur through onsite thermal or electricity storage and smart controls that alleviate demand and supply peaks. This in turn reduces high peak charges for building owners and tenants. While all new buildings should be designed and specified this way, existing buildings need to be rapidly electrified, made efficient and smarter.

Low embodied carbon buildings

As our electricity grid decarbonises over time, embodied carbon emissions play an increasingly important role. These are emissions generated from product manufacturing, transport and construction.

Infrastructure Australia estimates that an industry-wide: 'A 23% reduction in upfront carbon emissions is possible by 2026–27 by applying like-for-like decarbonisation strategies that that can be achieved by industry and government actively working together.'7

It is therefore important that Government projects set benchmarks for embodied carbon using the nationally agreed NABERS Embodied Carbon methodology.8

Climate resilient buildings

Australia is already experiencing the effects of climate change. Since records began in 1910, our mean temperature has increased by 1.5 degrees Celsius.9

Australia’s National Climate Risk Assessment evaluates climate risks across sectors including buildings and infrastructure.10

The increased risk of heat waves, droughts, bushfires, storms and floods means that we need to strengthen the resilience of our buildings and cities.

Projects should start with a comprehensive screening of climate-related risks by a suitably qualified professional. This will identify impacts to the health and wellbeing of occupants as well as to the infrastructure itself.

For example, a well-designed home with good insulation and shading can provide safer conditions for residents during heat waves than a poorly designed home that overheats and poses a health risk to vulnerable occupants. Similarly, a new public building can become a safer place for the community in bushfires, and landscapes can help absorb flood waters in storm events.

The Victorian Health Building Authority and the Department of Health have consistently improved the energy efficiency of their hospital portfolio with an average 4.1-star NABERS Energy rating across projects. New hospitals aim for high- performance, healthy environments and future proofing.

Benefits for the community

Health and wellbeing

Buildings and infrastructure are made for people and communities. We need comfortable conditions to thrive, whether we are at home, working in an office or learning at school.

Places where we spend significant time should all have good access to daylight and outlook, thermal and acoustic comfort and clean air. Embedding these objectives and specific targets in project briefs ensures that they can be delivered.

Our publication The Case for Good Design11 sets out the evidence-based benefits of good and sustainable design. A better investment Sustainable buildings and places are more adaptable to changes of use over time. This minimises the risk of obsolescence and costly retrofitting, while also reducing waste and depletion of resources. Sustainable buildings perform better as assets, both in terms of value and lifecycle costs.12

Nature

Regeneration

There is increasing evidence that reinstating natural landscapes in our cities has positive effects on people’s health and wellbeing.13 First Nations people have always known that we are deeply connected to the natural world around us.

Many projects can actively enhance nature in our cities, as well as reducing negative impacts on their immediate environments. This requires prioritising landscape and reinstating and linking fragmented ecosystems where possible.

To achieve net zero by 2050, all new buildings need to be net zero from 2030. A significant leap from less than 5% of new buildings today.

This project is part of a Melbourne Water program of works to ‘daylight’ underground urban waterways. The naturalisation of these waterway corridors provides opportunities for high-quality, accessible public open space, improved visual amenity and greater ecological outcomes. This project offers improved biodiversity, habitat and localised cooling benefits.

Aspect to address

Design for people

Humans are adaptable and resilient. However, continued exposure to pollutants, limited social interaction and sensory deprivation or overstimulation can affect health, wellbeing and productivity.

Buildings and our urban environment must therefore be designed with daylight, fresh air, acoustic comfort, outlook and connection to nature to support human wellbeing. This includes consideration for people of all abilities.

Environmental design

Good design begins with a deep understanding of the site and its broader environment. Project requirements should be interrogated with this in mind. A thorough assessment of climate, weather, wind, sunlight, noise, natural features and other environmental factors, needs to be undertaken early in the design process. Building facades should modify environmental impacts rather than rely mainly on mechanical services. This increases comfort and resilience while decreasing operating costs and risk of failure in extreme weather events.

Place

‘Place’ is more than location. It includes the cultural context and urban structure, as well as the natural setting and its history. Designs that enhance the existing qualities of a place are the ones that communities will positively embrace and care for over time.

Connecting with Country

First Nations’ concepts of Country go far beyond the natural environment, context and place. As stated by the New South Wales Government Architect:

'From green building practices and energy efficient technologies to regenerative landscapes, Aboriginal communities can lead the way in transforming the built environment to promote sustainability, resilience and community health. Their cultural practices reflect a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things, and a commitment to building a more equitable world for generations to come.'14

Adaptability and resilience

Successful buildings and precincts adapt to changing use patterns and conditions. Though future needs can be hard to predict, designs should use strategies and elements like structural grids and flexible layouts that can be easily transformed when required.

For climate resilience, buildings must be robust and able to maintain safe conditions even during power outages in extreme weather events. To achieve this, the design must include excellent passive environmental performance and facades that act as effective climate modifiers. Active systems such as on-site renewables with battery back-up may complement these passive strategies to ensure safe operations.

Flood risk may be addressed by directing and storing water in landscape as well as civil infrastructure, creating positive design outcomes.

Circularity and productivity

The construction sector generates about one-third of the world’s waste.

Effective procurement, design and engineering can eliminate waste and foster smart manufacturing and construction. When considered from the earliest design stages, this can also reduce construction costs. Victoria’s Recycled First Policy requires projects to optimise recycled content and reused materials.

Adaptive reuse of existing buildings should be thoroughly explored ahead of deciding to demolish.

As part of the new student precinct, the project is governed by Melbourne University's sustainability plan and target for carbon neutrality by 2030. The hall exemplifies sensitive, adaptive reuse, respecting the original heritage structure.

Climate positive

Climate-positive buildings neutralise or improve on their carbon impact. They are highly energy efficient, all electric and grid-responsive while also optimising the use of on-site renewables. Any make-up energy needs to use renewable power to operate at net zero carbon. Further, a climate positive building's embodied carbon is minimised and should be at least 4 Star NABERS Embodied Carbon. Finally, to compensate for the impact of the remaining emissions of the project, credible offsets are purchased.

The Victorian Government will build all new government buildings as all-electric, including new schools and hospitals.

The Woodside Building is a transdisciplinary facility for the Faculties of Engineering and Information Technology. It is one of the most energyefficient and innovative teaching buildings of its type. It was designed with Passivhaus metrics to create an ultra-low energy building with all-electric services, integrating purpose-built interactive learning and laboratory spaces.

What to do - by project phase

This section sets out the steps to integrate sustainability during each phase of your project. This advice aligns with the OVGA’s guide on procurement, Government as Smart Client.15

1. Vision statement + objectives

The vision statement guides expectations and decision making throughout the project.

• Provide clear aspirations for sustainability, human comfort, operational net zero carbon readiness, up-front (embodied) carbon reduction and resilience.

• Outline the aspects that are important to the project vision, such as the prioritisation of landscape and designing with Country.

• Set expectations for an integrated design outcome – rather than a disjointed sustainable management plan and sustainability features prioritised by cost to achieve a rating.

• Consider whether the project can set an example and serve as a learning opportunity for industry and the community.

2. Business case + feasibility

Developing a business case is a critical step to ensure support and funding.

• Explore alternatives to building a new asset and comprehensively assess the potential for adapting and integrating existing facilities.

• Apply whole-of-life carbon and costs in feasibility studies. This includes operations, maintenance, renewal, expansion, future adaptation and longevity of the asset.

• Ensure reference designs reflect the project’s aspirations, including net zero carbon readiness. A business-as-usual approach can result in insufficient budget and scope.

3. Client and design teams

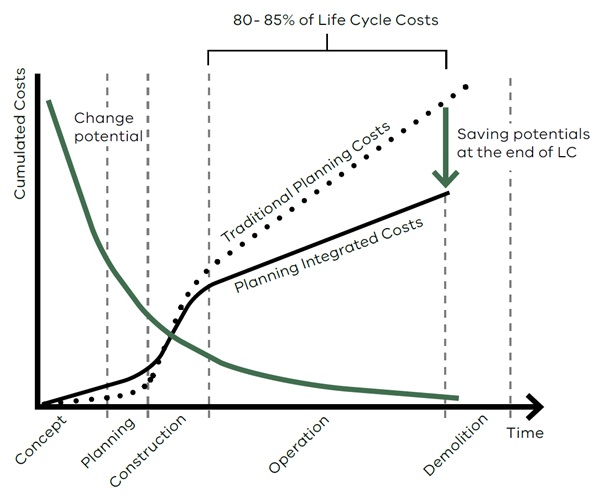

The cost of design services is very small compared with those of construction and life cycle operations, maintenance, upgrades and end-of-life, yet the quality of the design has a huge impact on these costs. Projects should engage highly qualified and experienced consultants who understand and can lead integrated, sustainable design.

• Invite only well qualified consultants to tender.

• When evaluating consultants’ submissions, assess value for money separately from the primary evaluation process, or set a budget for design services and evaluate submissions on quality and scope only.

• Identify a sustainability champion on both the consultant and the client sides. This will ensure a focus on sustainability throughout the project.

Costs in Integrated vs Traditional Planning

Kovacic, Zoller - Building Life Cycle Optimization tools for early design phases, Energy 2015 (ref. Jones Lang LaSalle, 2008)

T3 was designed with thermal efficiency, low carbon and low operational costs in mind. Its mass-timber construction, sourced ethically from local renewable forests, contains 34% less embodied carbon than an equivalent concrete structure.

The Bell to Moreland section of the Level Crossings Removal Project maximised spatial opportunities to provide parks, play spaces, pedestrian connections and cycle paths by incorporating elevated rail. As most carbon emissions came from concrete, the project identified and trialled innovations such as curing times and tensile strength materials. Working with the Infrastructure Sustainability Council of Australia (ISCA) and the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA), the line upgrade achieved the highest scores to date for both the line upgrade and Coburg Station.

4. Brief, targets and requirements

The brief translates aspirations into measurable targets and specific requirements.

• Optimise spatial and functional requirements.

• Explore the use and adaptation of existing assets.

• Consider the potential for spaces to fulfil multiple functions.

• Clearly articulate specific sustainability requirements and benchmarks.

• Include clear objectives and focus areas, such as health and wellbeing of occupants or biodiversity.

• Explicitly exclude fossil fuels use on site.

• Specify performance levels, whole-of-life optimisation and requirements for independent certification.

• Include post-occupancy evaluation in the scope to ensure learning and efficiencies feed into future projects.

5. Independent certification and benchmarking

Many government agencies have great internal capabilities in sustainability. Even so, seeking independent verification through recognised rating systems is critical. This ensures that project objectives are budgeted for, committed to by all parties and delivered throughout the process.

• Choose the most suitable rating systems for the type and scale of project. These should include design, asbuilt and operational phases of the life cycle.

• Include overall sustainability in the certification, as well as targets for energy, water, waste, embodied carbon and indoor environment quality.

• Consider recognised Australian rating systems such as NATHERS (design, residential energy efficiency), NABERS (design and as-built for embodied carbon, operational for energy, water, waste and indoor environment), Green Star (design and as-built across sustainability) and ISCA (infrastructure sustainability). International rating systems with particular focus areas that are recognised in Australia include WELL (design, operational, human wellbeing), Living Building Challenge (design, operational, broad sustainability) and Passive House (design, as-built, building fabric and air quality).

• Avoid ‘internal’ or ‘equivalent’ verification where possible. This risks insufficient rigour and assurance. It is easily compromised through value management.

• In small projects where certification costs may outweigh benefits, be very specific about particular performance requirements so they can be easily verified in design and as-built. Rating systems may still be useful as guidelines and to provide structure.

6. Design and documentation

Integrated design through early collaboration with consultants is fundamental to a good outcome. Hence, key sustainability strategies need to be developed from early schematic design and critical elements throughout documentation.

• Ensure all consultants share the project aspirations.

• Develop sustainability strategies, with highperforming passive design and mechanical services as complementary.

• Use environmental design modelling tools iteratively to inform the design.

• Explore and analyse the performance of options.

• Minimise up-front carbon emissions as per the NABERS embodied carbon methodology where possible. Aim for at least 4 stars.

• Design out unnecessary elements during the design process.

• Choose sustainable, enduring and healthy materials and finishes. Specify materials performance levels and credible product certification schemes.

• Optimise lifecycle performance and costs.

• Ensure services and appliances are highly efficient, all electric, grid-responsive and use electricity from 100% renewable sources, including on-site solar.

• Documentation needs to coordinate and detail all sustainability strategies to ensure their delivery and the achievement of certification.

• Include design review at key stages to ensure that strategies are scrutinised, optimised and protected. Contact the Office of the Victorian Government Architect for more information.

7. Managing value and cost

Value management is often misunderstood as construction cost savings only. While those savings are needed, the exercise is really meant to maximise value over time. Integrating sustainability from the start is key to optimising value and reducing costs.

• Uphold project aspirations and specific requirements while you explore alternative ways to achieve the requirements of the brief.

• Future proof for what you can’t yet fund.

• Consider lifecycle costs, including both for operations and maintenance.

• Consider an internal price on carbon, as recommended by Infrastructure Victoria.

8. Procurement and construction

Procurement impacts the quality of delivery and assurance of outcomes. For more information on how to choose the most appropriate contracting type and get the best value out of it, refer to our guide Government as Smart Client.

• Ensure that the builder has the capability and processes in place to deliver the project's aspirations.

• Include quality and environmental management practices and demonstrated experience in delivering certified sustainable buildings and infrastructure.

• Give design and sustainability consultants a line of sight to the construction process and the ability to inform any product substitutions and design changes. Consultants should also be empowered to communicate with the client.

• Include performance testing such as facade air tightness and thermography in the requirements.

• Ensure that subcontractors are briefed on all sustainability requirements and respective quality assurance processes are in place.

9. Commissioning operations

Many buildings do not reach their performance potential. This can be because commissioning is neglected, knowledge of design intent is lost, and buildings are not monitored and managed properly.

• Specify a rigorous commissioning regime and involve operators and facility managers.

• Ensure that the operational performance of buildings is reported against objectives and targets, including to consultants.

• Closely monitor and tune the facility for at least 4 full seasons, preferably 2 years.

10. Post-occupancy evaluation

Often omitted, post-occupancy evaluation helps optimise building performance and integrate learnings into future projects. It is a key part of continuous organisational improvement.

• Ensure continuous monitoring and improvement.

• Include independent post-occupancy evaluation in the project scope. Involve the design team, so that the design intent and performance can be compared and discrepancies can be identified and rectified.

• Make knowledge available within and beyond your organisation to support industry learning.

The Northcote Aquatic and Recreation Centre manages to remain sympathetic to its context while delivering a 50-metre new pool and outdoor space. A 6-star Green Star Design and As-Built rating was achieved - a challenging feat for an aquatic facility. Large scale photovoltaic arrays on the rooftop support all-electric operation. Three hundred cubic metres of mass timber and carefully incorporated daylight ensure a significant reduction of embodied carbon, while providing a warm, human-centred environment.

Good design

Only a well-designed building, piece of infrastructure, landscape or public realm can be truly sustainable. Places that are not only fit for purpose but also loved will be cared for, retained, adapted and used well into the future.

1. Inspiring Good design embeds the very essence of a project into a narrative and vision.

2. Contextual Good design is informed by its location and responds to its environmental, social and cultural conditions.

3. Functional Good design develops synergies between a project’s functional requirements and its vision.

4. Valuable Good design improves the quality of place and thereby its value. It enables the full potential for value creation and capture.

5. Sustainable Good design respects our environment and resources while fostering human health and well-being. It embeds daylight, fresh air, smart efficiency, sustainable materials, environmental repair and renewable energy in an integrated design.

6. Enjoyable Good design delivers inclusive and enjoyable environments that contribute to broader positive social and economic outcomes.

7. Enduring Good design synthesises vision and function. This embeds lasting value into our built environment and promotes community pride.

The spaces we design can either exacerbate global challenges or become powerful solutions.

Further Information

The OVGA website provides resources including this publication.

In-text references

01 Nationally Determined Contributions, 2025

02 Victoria's 2035 Emissions Reduction Target

03 Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings 2024

04 Sector Pathways Review, Built Environment, 2024

05 Every Building Counts 2023

05 International Energy Agency, Net Zero by 2050

06 Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront, World GBC, 2019

07 Embodied Carbon Projections for Australian Infrastructure and Buildings

08 NABERS Embodied Carbon

09 Australian Changing Climate

10 National Climate Risk Assessment

11 The Case for Good Design

12 The Business Case for Green Star Buildings

13 Nature in Cities

14 Connecting with Country

15 Government as Smart Client

Image Credits

00 Peter Bennetts

01 Tim Griffith

02 Diana Snape

03 COX Architecture and Billard Leece Partnership

04 Rory Gardiner

05 Peter Bennetts

06 Peter Bennetts

07 Tom Blanchford

08 Rory Daniel

09 Tom Roe

10 Tom Roe

Accessibility

Contact us if you need this information in an accessible format. Authorised and published by the Office of the Victorian Government Architect ©2025

Office of the Victorian Government Architect

1 Spring Street, Melbourne VIC 3000

ovga@ovga.vic.gov.au

Updated